Es gibt noch keine deutschsprachige Anmerkungen. Präsentiert wirden Anmerkungen auf English.

The archaeological site consisting of a Roman villa (villa rustica) in Višići (at “Kućišta”), with remains dating from Roman antiquity and the early and late mediaeval period (a Slav settlement and burial ground), Municipality Čapljina - National Monument of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Location

The Roman villa rustica at Kućišta in the village of Višići is located at an altitude of 20 m above sea level, latitude 43° 03.75.3' and longitude 17° 42.972'.

The National Monument is located on a site designated as the following cadastral plots: c.p. no. 821/1 and c.p. no. 821/1, title deed no. 910, c.p. no. 822/2, c.p. no. 823, c.p. no. 824/1, c.p. no. 824/2, c.p. no. 825, c.p. no. 1949, c.p. no. 1951/1 and c.p. no. 1951/2, title deed no. 858, c.p. no. 838, c.p. no. 840 and c.p. no.. 841, title deed no. 936, c.p. no. 839, title deed no. 613, c.p. no. 842 and c.p. no. 843, title deed no. 521, c.p. no. 862, title deed no. 249, c.p. no. 863, title deed no. 238, c.p. no. 1938 and c.p. no. 1939, title deed no. 11, c.p. no. 1940, title deed no.10, c.p. no. 1941, title deed no. 12, c.p. no. 1950, c.p. no. 958, c.p. no. 832 and c.p. no. 834/1, title deed no. 987, c.p. no. 826/1 and c.p. no. 826/2, title deed no. 203, cadastral municipality Višići, Municipality Čapljina, Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Historical background

Modern-day Čapljina is on the Roman road that ran along the Neretva valley from Narona(2) to modern-day Mostar. It was a sizeable Roman settlement, as confirmed by the ruins of Roman buildings, and numerous finds of antique coins(3) and imported pottery. The proximity of Narona and the favourable geographical location contributed to the growth of the Roman settlement in Čapljina, which became a trading and communications centre for the surrounding areas. There were sizeable Roman settlements along the Neretva to the north of Čapljina in Dretelj, near Počitelj, and in Žitomislići. The entire area from Čapljina to Narona and Hutovo Polje was one of the most densely inhabited areas of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Roman times(4). Narona, a Roman colonia in the southern Adriatic, extended back deep into the hinterland, its ager covering almost the whole of modern-day western Herzegovina. To the west, it extended to the Imotski polje, where it marched with the municipium(5) of Novensium (Runovići near Imotski), and to the north-west with Delminium (the municipium of Delminensium) in the Duvno polje, both in the lands of the Delmatae tribe. The municipium of Diluntum (Diluntinum, Stolac) was on the left bank of the Neretva. The colony's large area was probably subdivided, for ease of management, into smaller units or prefectures, and later into pagi (sing. pagus). These were in fact small natural entities, the location and extent of which can be deduced from the lie of the land (Ljubuški, Brotnjo, Čapljina, Cim). The entire area was under central administration from Narona, where the senate (ordo decurionum) had legislative and administrative authority over the colony's entire ager. Representatives of out-of-town decuria (decuriones) also came to the council; at first, these were mostly large landowners, but with time they were joined by a few local notables(6).

The process of Romanization and urbanization, which began in the lower Neretva region a full century and a half before it reached the hinterland (the upper Neretva and Bosnia), peaked in the 2nd century CE. The development of urban settlements, one of the most significant forms of Romanization, began here in the 1st century CE (Narona, Humac, Posuški Gradac, Stolac, Tasovčići, staging posts etc.). New building techniques, forms and structures were used, unknown in the region before the Romans introduced them. The traditional timber and dry-wall structures were replaced by new materials (lime and mortar, cut stone, fired brick and so on). Evidence of the early presence of Romans in and around Čapljina is provided by an inscription from Tasovčići, erected in 36/35 by the brothers Papii in honour of Octavian (CIL III 14625), which is also the earliest Roman inscription yet found in Bosnia and Herzegovina(7).

Numerous Italic-type settlements took shape throughout the colony of Narona, most of them during the early Empire. There are settlements of this type around Ljubuški, Čapljina and Čitluk, with some around Grude, Posuški Gradac and Široki Brijeg, as well as by the Radobolje near Mostar, with its centre in Cim and Ilići. The most common type of structure in these groups of buildings is the villa rustica, forming the centre of a smallish farmhouse estate (fundus, praedium); such estates would sell their surplus on the market. In time small-scale manufacturing also developed on such estates, usually brickworks (figlinae), producing tiles and bricks, for which there was a great demand, but also those of other trades – stonemasons' yards, smithies, carpenters' workshops etc. Very few of these commercial estates have so far been excavated: one that has, is the large villa in Višići near Čapljina.

Description of the property

Remains of the villa

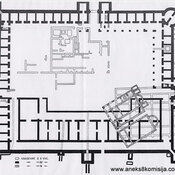

The villa as so far excavated consisted of a number of buildings, including the lavishly appointed main residences occupying the central area of the estate. These were interconnected, surrounding courts of various sizes. On the outer edge of the group of buildings was a boundary wall wherever there was an open court, sometimes quite large. The courts have been excavated only to the extent of small soundings along the walls. The complex therefore consisted of a group of buildings, some detached, forming a separate entity, usually separated by walls. The first group of buildings, to the north-east, surrounded a brick kiln and open area I (building A). The next was a peristyle building(8) (building B). A building with a hypocaust(9) (building C) extended from the south-east corner of building B; beyond building C was court IV, with workshops. The south wall of court IV continued eastwards, enclosing court V facing the south façade of the peristyle building. A range of buildings led from the north-west corner of the peristyle building to a building D, the northernmost building of the villa. Building D consisted of a long building to the south, probably the bath suite, and adjoining buildings to the west and north, forming a U-shape surrounding a square court and thus dubbed the “U-buildings;” all three had a portico facing onto the court, which interconnected them(10).

In this group of buildings, the main, lavishly appointed buildings (B, C and D) were all oriented south-east/north-west, and reveal a tendency towards architectural regularity and symmetry. Seen as a whole, however, the group does not convey a sense of symmetry, since the walls of the service quarters were not in line with those of the main buildings. This layout was no doubt dictated by the practical needs of estate management.

The purpose of the various groups of premises could be determined only on the basis of their surviving architectural remains and any finds made within them. In places, especially around the outside of the villa, the ruins of the walls had been much dispersed, and the Slav settlement and burial ground had caused significant damage to some of the buildings, which is why it has proved so difficult to shed light on the architecture of the villa in Višići.

Judging from the surviving walls in building B and, to some extent in building C (elsewhere, only the foundations survived), the walls were of fired brick and the foundations, which were 50 cm wide, were of rounded stones set in a conglomerate of mortar and gravel. The foundations were 60-70 cm in height except in the case of the hypocaust, where they were higher, to accommodate the height of the pilae stacks. The walls were of wedge-shaped bricks laid in courses, known as opus testaceum, using the large bricks known as tegula bipedalis, set with their long side outwards, framing a core of mortar and gravel. This type of brickwork was common in Rome from the reign of Claudius(11) (1st century) onwards, and remained in use until the late 2nd century. Part of the wall had survived in the south-east corner of the south façade of the peristyle building, enough to conclude that the south façade had been built in opus reticulatum, using small, diamond-shaped bricks. Like opus testaceum, this technique also first appeared during the reign of Claudius, and remained in use until 180. This wall belonged to a later stage of construction, being used for only one side of the building. By Vespasian's reign(12), only prominent wall faces were built in this technique, and from Trajan(13) to Aurelius(14) the use of opus reticulatum gradually declined.

Building A

The group of premises forming the north-east end of the villa could not be properly excavated, since much of the group lay beneath family houses, and the remains of the easternmost premises had seemingly been swept away by the river that once flowed here, where the road now runs. Evidence for this can be found in the vestiges of walls on the opposite side of the road, in the fields, where the easternmost corner of the villa probably lay. The rooms of building A were separated from those of building B by a court, with only room 10 at the northern end of the court connecting them with the north and east premises of building B. A brick kiln divided building A into rooms to the south and others to the north, probably each used for different purposes. The four rooms to the south (1-4 A), faced in the same direction as the peristyle building. It was not possible to excavate their north-east corner, which lay beneath an orchard(15). The two oblong rooms at the south-east end were irregular in shape, with their north wall on the diagonal to accommodate the brick kiln, which was off true towards the west from the north-south axis, as were the rooms to the north. The two irregularly-shaped rooms (2 and 3A) where the remains of large vessels and amphorae were found had floors of lime mortar. Another two rooms (1 and 4A), which opened onto court I, had no flooring, but contained a layer of small lumps of reddish and yellowish unfired clay waste, roughly 10 cm thick. This group of rooms, like nos. 5 and 6A, were probably used as workshops associated with the brick kiln. The larger, 6A, belonged to the original building, while 5A was a later addition, as the walls built on a half-metre thick layer of rubble indicated. Quantities of potsherds were found in the north room, 9A, probably rejects from a pottery, since they included two bases of vessels that were not up to standard. The finds in the south rooms were sufficient to provide a fairly clear idea of their use, but the use of those to the north of the brick kiln remain a mystery, particularly since they could not be excavated. All that could be traced was their west wall, which extended on by more than 15 m to building B, thereby forming the boundary wall of open area II outside the peristyle building and probably the bath suite (building D) as well. This group of rooms seem to have consisted of two ranges of rooms, of which only the first two (7 and 8A) could be excavated, in part. Since the level of the topsoil in room 7 was more than half a metre below that of the topsoil in room 8, and given that the circular bricks of pilae stacks from a hypocaust were found in the ruins, it seems likely that these rooms had a hypocaust, as did those further along, as suggested by the bricks of the type known as tegula mammata (which replaced the box flue tiles known as tubulus)(16). The hypocaust suggests that these rooms were used as living quarters, or perhaps as a kitchen, since they were close to the triclinium in the north wing of building B(17).

Room 10, which connected buildings A and B, differed from the rest. Its profile revealed that it had been used to store amphorae, probably holding oil and wine. Like all the open rooms, this had no flooring; above the top soil, at a depth of 150 cm, was first a 40 cm thick layer of sand, in which there were sherds of amphorae, the thickness of the layer indicating that the amphorae were set into the sand. This room must have been used a wine and oil store for building B.

The brick kiln occupying the middle of building A was quite large (5 x 10 m), square in shape, with a single central channel 50 cm wide and 30 cm high with six narrower side channels branching off. Only the substructure of the kiln had survived. The door for feeding fuel had been destroyed by three later Slav burials. The kiln is of the type used for firing bricks, as suggested by two large piles of unfired roofing tiles (imbrices) that had become fused together, found not far from the kiln in the portico and garden of the peristyle, and by the remains of clay in the workshops next to the kiln. No waste matter of the kind that could have provided firm evidence for the type of wares fired here was found around the kiln itself. Square kilns were not used only for firing bricks. Square kilns have been found in Helvetia(18) and Pannonia that were used to fire pottery. Square pottery kilns predate circular ones, found for instance in Germania, and first appear in Pompei in the 1st century BCE, whereas circular kilns appear only in the 2nd and 3rd centuries. A square kiln found near the Ali Pasha mosque in Sarajevo was probably also used to fire pottery(19). Since the upper part of the kiln in Višići had been completely destroyed, it is impossible to say whether it was also used to fire pottery.

Building B

Building B – the peristyle building – proved to have the usual regular layout of rooms around a central garden: one range of rooms to the east and one to the west, and two to the north, with a narrow portico on the north and south façades. Judging from the small surviving area of wall at the east corner of the façade, the south façade was faced on the outside with small diamond-shaped bricks in the technique known as opus reticulatum. The roughly square open central area of the building (13 x 14 m) had no floor, and might have been a garden. It had a double wall, the outer probably forming a base for the columns of the portico, and the inner, 20 cm lower than the outer, either a retaining wall or a step. None of the stone fittings of the portico and garden were found here, and neither were any vestiges of the peristyle columns, apart from a fragment of a single column with a diameter of 13 cm. Most of the artefacts found in this complex appeared to have been brought from elsewhere. Artefacts found in the 15 cm thick cultural layer about 150 cm below the surface consisted of both Roman and Slav articles intermingled, potsherds, tools, pieces of Slav jewellery and a semicircular bronze seal with the name of an officina (workshop), MAXENTIA, no doubt from the workshops, like the lump of waste from roofing tiles.

The garden was surrounded by a colonnade of which the quite badly damaged floor consisted of a 30 to 40 cm layer of sand topped by rammed fine-grade crushed brick. This was probably level with the mosaic floor.

The living quarters surrounding the garden were elaborately decorated. Most of the floors were of mosaic, and there were murals and stucco friezes on the walls, which had marble-clad dado panels. The corridors had simple mosaics with blue designs. The floors in the rooms were in polychrome, except for rooms 4, 6, 8, 11 and 15 B, which had floors of lime plaster, though the walls were elaborately decorated with murals and marble cladding. It is possible, therefore, that the floors were plastered when the mosaics were damaged, as happened in rooms 7 and 8, originally one room.

The mosaics are certainly the most valuable survivals in the rooms, being in a better state of preservation than the murals, enough to be reconstructed. The only mosaic that was completely destroyed was the one in room 4B, though those in rooms 1, 2 and 23 B were quite badly damaged; the others were damaged only in places. In room 18 B, later repairs to the mosaics were observed, where damaged areas had been filled with larger tesserae than were originally used.

The architecture of this building showed a tendency towards symmetry, with the east and west ranges of rooms of the peristyle almost identical in layout and size. This symmetry was also reflected in the principal motifs of the mosaics, with any monotony in the repetition avoided by the choice of different designs as fillers. In rooms 2 and 23 the central motif was a circle with a rosette with rhomboid lobes. In rooms 3 and 22 the central motif was again a circle, filled with a diamond pattern (room 3), or with a fish-scale pattern (room 22); in each case, the centre is occupied by fish on a platter. The corresponding corridors, 5 and 19, had a simple pattern of small crosses. Rooms 17 and 8 had a design consisting of a central circle filled with seven hexagons. The north rooms of building B again feature symmetry. The largest room, in the middle, was the triclinium, with an elaborate mosaic floor; its size, central location and lavish decoration highlight its importance as the main dining and banqueting hall. It was flanked on either side by two symmetrical rooms and a corridor, where the motif consisted of diagonal interlocking circles. The floors of the two facing rooms by the colonnade were of lime plaster (11 and 15 B), while the ones by the north porticus (10 and 16 B) had mosaic floors with designs based mainly on squares.

It was not possible fully to determine the circulation from room to room in building B, since not all the walls had survived to above floor level, and in places neither had the thresholds. The only indication of the construction of the thin partition walls, which were largely ruinous, was the remains of two sizeable blocks that had survived in the layer of rubble on the floor in rooms 10 and 11 B, consisting of pieces of thin roofing tiles laid diagonally in a thick layer of mortar. Doorways were identified between rooms 1 and 2, 5 and 6, 7 and 8 B and 8 and 10 B, as well as one between the corridor and the colonnade, in the case of the east rooms. The central room to the north had four doorways opening onto the side corridors direct from the portico.

The symmetry of the east and west rooms of building B was disrupted by the small rooms at the west end of the west rooms. Most of these appeared to have served the same purpose, to provide indirect heating for the west rooms against which they abutted, since the pilae stacks of a hypocaust were found in them. Rooms 22 and 23 B ended in the form of apses, connecting to the point at which the hot air vents met. The praefurnium had not survived.

Another group of four small rooms, all quadratic in plan, occupied the north corner of the west rooms of building B. The first three rooms consisted of a central longer room without flooring (28 B), flanked on either side by small rooms both of the same size, with the pilae stacks of a hypocaust. The room with the pilae stacks had a vent opening into the large room in the middle, which probably provided direct ambient heating. The fourth room (30 B) was of the same small size; at the extreme north-west corner of the peristyle building, it was used as a privy, and had a flooring of large flagstones. Another small room, a later extension, also formed part of this range, and was used as a kind of passageway from the corridor into open court II.

The elaborately decorated rooms of building B were no doubt used as reception rooms and as dining or banqueting halls, as suggested by finds of terra sigillata chiara and shells(20).

Building C

This residential hypocaust building, quadratic in plan, could not be isolated from the other rooms with court IV, forming as it did the north-east corner of that building. Abutting onto it were rooms leading onto the court and surrounding service quarters. There were also three small rooms by the square room; it proved impossible to determine whether they were connected with building C or had had some other specific purpose. The small south room, 12 C, was heated by the hypocaust of this building. The flooring in the rooms of this building had suffered more than those of building B, since the level of the hypocaust was somewhat above that of the rooms in building B, which was one of the reasons why not one floor with pilae stacks had survived. Here too the flooring above the pilae stacks had not survived, and only some remains of the pilae stacks themselves remained. Even the floors of the rooms with no pilae stacks were badly damaged, being only half a metre deep in fields that were regularly ploughed. In rooms 2 and 4 C, only the base for the mosaic had survived; the tesserae were found in the rubble below the floor. The floor of room 5C was at the same level; fragments of its lime plaster flooring were found in the rubble. Rooms 10 and 11 C with pilae stacks would seem to have had mosaic floors, given the number of tesserae and fragments of red wall painting that were found in the rubble between the pilae stacks. Only the small room above the praefurnium had no flooring, being used to fuel the praefurnium.

The substructure of the hypocaust rooms were better preserved. The praefurnium, with a flue providing direct heating for room 10 C, also provided heating for rooms 11, 1a and 12 C, which were interconnected by hot air flues in the walls. Later the flue in room 11 C was bricked up. In all these rooms the pilae stacks of the hypocaust were of circular bricks with a diameter of 20 cm, except for the pilae stacks against the west wall of room 1 C, which were of square 30 x 30 cm bricks.

Judging from the hypocaust and its fittings, the mosaics and the murals, this would certainly have been a dwelling house, as further evidenced by the construction system of the hypocaust. The praefurnium flue was not by the bath suite, outside the room, but was built into the first room itself. Setting the pilae stacks of the hypocaust right by the wall made it impossible to use tubuli(21) by the wall, essential in bath suites to protect the murals from damp. Another opinion is that the tubuli were used not only to damp-proof the murals but also to heat the walls. It is not clear what the rooms heated direct without a praefurnium were used for, such as rooms 9 C, 27 B and 29 B. They are thought to have been small supplementary hypocausts to provide greater heating for a given room, which would correspond to the use of the small rooms on the west side of the peristyle in Višići(22).

The way the hypocausts in Višići were constructed matches that of the third, more advanced stage in the development of the hypocaust. The bricks used were extremely heat-resistant, making it possible to achieve very high temperatures, sufficient for one praefurnium to heat as many as four rooms. Hypocausts of this type were first built in the late 1st century.

The hypocaust building formed a single entity with south-west court IV, forming as it did the north side of the court, along with the room with a well. The east wall of the court was an extension of the east wall of room 12 C, and the west wall an extension of the west wall of the room with a well (8 C). A range of large rooms, 14 m in width, 21 to 24 C, abutted onto this west wall. The south wall of the complex could not be traced for technical reasons. All that survived of the walls of the large rooms was the lower course of rounded stones of the foundations, as in the other outer rooms of the villa. The cultural stratum was poor; just a few potsherds were found.

The finds in the other rooms around the court revealed that there were workshops here. Large estates such as this one in Višići always had all the workshops needed for the household. Some could not be traced, since the Slavs had dismantled all the fixtures in the buildings and used them to build a hearth in building D, in the north-west corner of the villa complex (the bath suite). Judging from the remains in this court, the workshops here would have been used for preparing clay, and would also have included a forge and other workshops. This was suggested by finds in the narrower part of the court, by room 8 C, of iron stoneworking and woodworking tools, a bricklayers' trowel, and pieces of slag – waste from a forge. Fragments of amphorae, unfired potsherds and blocks of fired earth were found in room 13 C, suggesting that this was a pottery, which the Slavs later completely destroyed: the lower stratum contained not only Roman pottery but also sherds of Slav pottery and the remains of children's skeletons. A range of small rooms (14 to 20 C) in which a 20 cm thick layer of clay waste, green and yellow in colour, was found, would have been used for preparing the clay. These rooms were next to the room with a well (8 C), from which the workers would have drawn the water they needed. The stone well was square, and covered with stone slabs, only those by the west corner surviving.

There was no sign of flooring in any of the rooms in these service quarters, which probably had lime plaster floors.

Building D

The third dwelling house, with its elaborate stone furnishings, formed part of a group of buildings surrounding three sides of an open square space and connected by an inner colonnade. The main building was connected with building B by a range of small rooms. Here the walls, which were 20-30 cm thick, were of poorer construction than in the other buildings. This poorer construction, the finds of pieces of amphora, potsherds, pestles and mortars, and shells, suggested that they formed the kitchen quarters, or were storerooms. In building D, the main building stands out on account of its elaborate stone furnishings, its architecture and its use, and appeared to have been self-contained. The west and north buildings of building D, forming an extension of it, would appear from the finds to have been much less important.

Evidence for the existence of a bath suite in building D is provided by the substructure of a hypocaust and a water supply system. Since the flooring of the substructure was missing in almost every room, it was possible to deduce only from clues whether certain rooms had pilae stacks. In the large room, 9 D, which had a range of small rooms to the north and south, the lime plaster flooring had survived in two small rooms to the north (4 and 5 D) and in the oblong room at the west end (10 D). The depth of this flooring matched that of the flooring of the substructure of the hypocaust rooms of building C. Circular brick stacks were found on the floor in room 10 D, probably in situ. No evidence of a praefurnium was found; it was probably outside the building, as in the case of every bath suite. Coarse mortar with an admixture of finely crushed brick in the surviving foundations in room 10 D suggest that there was no floor at this depth. The walls of the room, however, were painted, as revealed by the remains of red wall paint on a small area of the wall of the latter room.

There is evidence of temporary hearths(23), but the Slavs also built numerous permanent hearths, where up to 30 cm thick layers of red baked earth were found. The hearths were not in the metre-thick layer of rubble, as alongside the Slav graves, but were built amid the foundations, or in some cases above them, at the level of the hypocaust substructure floor, which had not survived. They built hearths in the small rooms 3, 7 and 8 D, by piling up large stone blocks from the substructure of the building and the large bricks connecting the hypocaust pilae stacks and serving as underflooring. The facing of the capital of a pilaster was found beneath the hearth. The circular stone from an oil press and stone weights were found in room 16 D beside a temporary hearth; these do not belong to this building, but were probably brought here from the nearby rooms around court IV. Signs of a water supply system found alongside the large room with small partitions by the south and north walls suggest that these were some of the rooms in the bath suite(24). Part of a stone channel to take water into the large room, 9 D, had survived in the floor of room 18 D. The next room, 19 D, had a cold-water pool, of which only vestiges remained (the lower course of rounded stones on three sides of the pool, at a depth of 1.50 m).

The architecture of this building was very similar to that of other Roman baths, and in particular to the layout of bath suites in the large villa known as Sette Bassi near Rome, which differs only in being rather larger and in having more side or utility rooms. This resemblance is particularly marked in size, form and vaulted construction(25) of the two large rooms (2 and 9 D) corresponding to the same rooms in the villa Sette Bassi(26). All the indications are that room 2 D must also have been vaulted in this way, as in the villa Sette Bassi, as suggested by the great width of the room and the two short side walls, of which vestiges had survived, and of which there were probably more.

The other large room in the villa in Višići, with its several small booths along both side walls, is also similar in layout to the other large room of the villa Sette Bassi, the tepidarium(27). The remains of tufa and the ground plan of the room suggest that it was partly vaulted. Finally, the villa in Višići had the same portico by the small rooms as did the villa Sette Bassi, where there are further rooms beyond, whereas in the villa in Višići the complex ends after the frigidarium(28) with a group of rooms probably forming the main, formal entrance to this building(29).

In Višići a further group around the entrance consisted of a large room open to the north (21 D) and three smaller ones by the south wall (20, 22 and 23 D). The group ended with two irregularly-shaped rooms (24 and 25 D) where the flooring had not survived. The base of a column was found in the north-east corner of the room by the short (1 m long) north wall, as were fragments of a column with a diameter of 28-30 cm. The remains of stone furnishings were found in the south booths of room 9 D, and fragments of a Corinthian capital were uncovered in the small booth as D. The building was quite badly damaged, and it was hard to determine where the various architectural elements belonged, since it was possible they were not found in situ. The westernmost part of the building was also badly damaged by later Slav settlement, with only the lower course of the rounded stones of the foundations surviving in places. The Slavs built a hearth over the partition wall of rooms 21 and 25, using the larger flooring bricks scattered around the building. This hearth was 5 m in diameter, with a half-metre deep cultural stratum of organic waste with animal bones around it.

Soundings only were taken in the west and north ranges of rooms of building D.

The architectural remains, of which little had survived, reveal that the villa was richly decorated with stone and marble. Most of the marble was in the building that was probably a bath suite (building D). Among these finds were three fragments of Corinthian pilaster capitals and the marble facing of pilaster capitals. The architectural finds in the bath suite were as follows:

- fragments of Corinthian capitals in room 11 D, from which three capitals were reassembled, but could not be fully reconstructed

- the facing of pilaster capitals; the fragments of one entire and one broken marble facing from pilaster capitals were found in the ruins of the bath suite. The motifs on the facing were in bas relief and were executed with great precision

- the conical base of a pilaster

- three broken square pillars 168 cm in height

- the base of a column from room 21 D

- the fragment of a column base

- the top section of a column

- the middle of a column

- a fragment of impost-capital

- an architectural terminal in the form of a sphere below which was a fragmentary conical section with a shell ornament

- fragments of columns with a diameter of 13 cm from building B

- a fragment of architrave with mouldings on both sides.

The material (carbonate stone) used for the stone furnishings of the villa in Višići was probably of local origin.

The most common finds in the ruins of the villa consisted of wedge-shaped building brick, mainly red, and light yellow roofing tiles. Among the brick used in the hypocaust rooms, the most numerous finds were those used in the pilae stacks, mostly circular, varying in diameter; square bricks were less commonly used. The roofing tiles found in the greatest number were the half-round tiles known as imbrex or tegula imbricata and the flanged tiles known as tegula. In building B, trapezoid and wedge-shaped tiles with a stepped profile were also found, probably forming part of the frieze in the peristyle colonnade. Some of these bricks could have been fired in the workshops of the villa itself. This is certainly true of the imbrices, given that a large clump of fused unfired imbrices was found in the peristyle garden. The wall bricks and floor tiles were probably also made on site, since fragments of unfired brick were found in the small rooms by the well (rooms 14 to 20 C). The tegulae, on the other hand, seem to have been imported from other workshops, as suggested by the die-stamps of the following workshops found among them:

PANSIANA: two fragments were found with this stamp, in rooms 9 A and 3 C, though only the last two letters had survived, making it impossible to identify the variety they belonged to. Trieste is believed to have been the centre of this workshop(30). Bricks from this workshop are found in Dalmatia and Narona, Imotski, Gradac, Stolac and Čapljina. Though this workshop is known to have become an imperial officina under Tiberius, and that this stamp ceased to feature from Vespasian's reign, it was no use for dating purposes, since bricks from this workshop survived in places long after it closed down (e.g. in the basilica in Klobuk, as late as the 5th century).

COELI: two fragments were found with this stamp in room 9 A. This stamp has been found to date only in Asseria and Narona. The centre of the workshop seems to have been in Istria and Aquileia.

L.EPIDIUS THEODORUS: a fragment found in room 9 A. The same stamp has been found in the Trieste area. Stamps with the names Caius and Marcus Epidius are also found in Salona, and in Narona a stamp was found of C. Petronius Aper EPID. K. Patsch is of the view that these are the names of lease-holders of Epidius' figlina. The name Epidius also features on pottery.

T.R.D.: a fragment found by the west wall of room 22 B; also found, in the variant T.R.DIAD, in Pula, Salona and Aquileia.

M.VAL.DO: found in room 9 A; so far [previously? Trans.] unknown here.

(C.TIT) I. HERMEROTIS: found in building D;

MAXENTIA: the original semicircular bronze die stamp was found in the peristyle garden. In shape it resembles the die stamps used to mark bricks in the 1st century. The name of this officina, however, suggests a date in late Antiquity.

Rarer architectural finds include an entire antefix and the fragment of an antefix with a head of Medusa in relief. Both were found in the garden of the peristyle building, to which they probably belonged. The Medusa's head is quite stylized, with the hair more like a diadem, and what looks like a palmette-shaped pendant on the forehead instead of serpents' heads. The expression on the Gorgon's face is impassive rather than fearsome; the head thus belongs to the peaceful Gorgon type, fairly common in Roman times (a peaceful Gorgon has been found in Šipovo, similar in form and with the same peaceful expression, but of finer workmanship and with no tendency to stylization). The Romans regarded Medusa as a protectress and household goddess; her image on an antefix served to protect the house.

A circular stone (area), the base of an oil or wine press, with a circular groove around the edge (canalis rotundis), was found in the bath suite 9 D of the villa, in a secondary location. Since the primary location of the press was not identified, and no other parts were found, it was not possible to find an exact analogy for it. Two large stone weights of the usual biconical shape were found by the stone from the press, doubtless from the service quarters.

Mosaics

The mosaics in the building with the peristyle are among the best-preserved architectural remains. Though damaged in places, it was possible to reconstruct all of them. It would appear that during the Slav period the mosaics were covered by a thick layer of rubble, which helped to maintain the flooring in a better state of preservation than in the bath suite of building D. The Slavs dug graves only in places in the building with the peristyle (B). These mosaics lacked the usual solid foundation, but were laid on a base no more than 25 to 35 cm thick, consisting of a layer of fairly large pebbles set in the soil and topped by just 13 cm of fine gravel and mortar, with a final coat of fine plaster into which the tesserae were set. This less than usually solid base had resulted in most of the mosaic floors sinking unevenly, especially in the middle, sometimes by as much as 10 cm, resulting in quite serious damage.

The materials, techniques and motifs used for the mosaics were the same throughout, which indicates that they were all of the same period. All were of geometric design, enlivened here and there with marine animals and conventional motifs. The tesserae used to form the border were larger than those used to form the central motifs. All the mosaics had a white ground, with red, light red, yellow and blue-grey as the predominant colours. In Višići, blue-grey tesserae were used instead of the more usual black, giving the mosaics softer, lighter tones. Most of the mosaics are polychrome, using the same four colours. A few (those in the corridors and antechambers, which are smaller in size) are in white and blue-grey only.

Mosaics with a central motif feature in two variants. In the first, the central circle occupies the entire surface, with an ivy-leaf design in the corners or a triangular panel of white and blue triangles (in room 22). Both mosaics have a central fish motif in dark and light red on a yellow platter with a stylized geometric handle. The central circle also has a pattern consisting of eleven concentric circles of scales. The mosaics in rooms 2 and 23 B consist of the second variant on the theme, with the central circular motif set in a square, around which are quarter-circles in the corners and semicircles along the sides of the square, and a ring of triangular sections of spheres with concave sides between the central circle and the half and quarter circles. Another mosaic belonging to this group of central motifs is the one from room 16 B, with a central motif composed of a diamond shape surrounded by a cable twist.

Mosaics with repetitive geometric motifs fall into two groups: simple designs and more complex one (the latter often enhanced by the cable twist surrounding the motif). The simpler designs consist of a single repeated motif – contiguous circles around a diamond shape (room 20 B)(31). Monotony is avoided in the case of the mosaic in room 18 by alternating rosettes composed of four diamond-shaped lobes and squares containing, alternately, quarter-circles or four stepped triangles at the corners, thus covering the entire surface with geometric motifs. The most elaborate mosaic is that in room 13 B, with three basic motifs: a rosette composed of four triangular lobes, a square, and an octagon surrounded by a cable twist. The longer, narrower panel of this T-shaped mosaic is decorated with a less elaborate motif of continuous rhomboid swastikas set transversely above the main panel of the mosaic, in the cross-bar of the T. T-shaped mosaics of this kind are typical of triclinia.(32)

Among the motifs used to fill the panels of the mosaics are both marine animals – fish, dolphins and stylized shells – and plants: palms, calyces, acanthus leaves, ivy leaves. All the mosaics have a simple outer border in blue and a more elaborate polychrome inner border (usually a tricolour cable twist on a blue ground).

The mosaics from Višići show a considerable degree of diversity in both design and motif. Central designs taken from Hellenistic Greek mosaics, with secondary motifs dominated by the central motif, and designs consisting of repeated geometric motifs, which first appeared on Roman mosaics, are almost equally represented. Both are found in other Roman provinces as well: only the motifs filling them display great diversity in the way they are combined. There are no other geometric mosaics closely analogous to these in this part of the world, since most of our sites date from late Antiquity. The designs and repertoire of motifs of the mosaics are almost identical with Italic mosaics, in particular those from smaller villas in the region of Rome(33).

Based on studies to date, the mosaics from modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina largely date from the 2nd to the 4th century(34). Judging from the composition, mainly in black and white, of two examples (one from the Zenica region and the other from Višići), these would be the earliest mosaics from this country, dating from the 1st century. Roman mosaics became increasingly popular and widespread in the 3rd century, but the art began to decline in the 4th century. The mosaics from Carina in Sarajevo, Crkvina in Panik and the badly damaged fragment from Japra indicate that mosaics were still being made in Bosnia and Herzegovina for early Christianity in the 5th and 6th centuries. There was a major centre of mosaic work in Salona in the province of Dalmatia. Other important centres of mosaic workshops, from which the artisans came who made the mosaics in Višići, Stolac, Panik, Ilidža and Domavia, were in the towns of Epidaurus and Narona(35).

Murals

The murals had suffered particularly badly in the scattered ruins of the villa. A few fragments, insufficient to reconstruct any of the murals as a whole, had survived in some of the rooms, particularly in building B; in the hypocaust rooms (building C), on the other hand, most of the murals had been completely destroyed. The ornaments and colours of the murals are similar in all the rooms, and would seem to date largely from the same period (c. 190 to 220 CE). Judging from the number of red, yellow and white fragments and the surviving remains of wall painting at the base of the walls, the panels into which the walls were divided would have been in these colours. The differently-coloured areas of wall were separated by bands of various widths and by frames. The only survivals from the scenes within the panels consisted of fragments of vegetation and birds. The motifs of the murals match those of other murals in the surrounding provinces, and belong to the late Antonine style.

It was not possible to date any given mural room by room on the basis of the few and varied surviving fragments, but only to obtain a general impression of the way the walls were decorated and the style of the murals. The surviving fragments of murals suggest that they date from the latter half of the 2nd century, when the Antonine style was replacing the classical, phil-Hellenistic style in which walls were articulated into lower, middle and top registers by depictions of architecture as the setting for various scenes. During Antoninus' reign, the architectural background was gradually abandoned for broad frames, which replaced it entirely by about 190 CE. Much of the fragments of wall painting found in Višići date from the period between about 190 and 220 CE, characterized by decorations in which the registers were separated in equal proportions by broad and narrow bands. Since the same fragments of murals were found in the bath house as in the other rooms, and the capitals found in the bath house dated from the 4th century, it would seem that most of the murals, with some later touching up, survived into the 4th century(36).

Roman pottery

The largest group of finds from the villa in Višići consisted of Roman pottery, found in disturbed strata throughout the part of the villa that was excavated, except for the room around the well. Despite the quantity of sherds found, very few vessels could be reconstructed. The largest quantity of sherds was found in room 9 A near the brick kiln and around the well. The lower cultural stratum and the layer of rubble contained Roman pottery intermingled with Slav pottery, which would have sunk to a deeper stratum when stone was being removed from the walls and graves were being dug.

The most common finds of Roman pottery were of light-toned and red wares, mostly of fine grade clay and sigillata chiara(37). There were very few sherds of Belgian grey and black wares, which are among the most common finds in the northern provinces, or of marbled wares and those decorated in colour, mainly with stripes. White-painted wares were somewhat more common. Most of the finds of chiara were around the peristyle building; only occasional sherds of this light samian ware were found in the other buildings. Fragments of chiara ascribed to the 2nd century were found in the bath house, the stone furnishings of which date from the 4th century, suggesting that this building must have been in existence in the 2nd century.

The marbled wares fall into two groups. The earlier, dating from the 1st to 2nd century, is fine ware decorated in light red applied with a sponge; the later is coarser, with dark brown decoration. Two of four sherds found belong to the earlier group and two are of later date, 3rd to 4th century. Three other sherds decorated in colour could not be accurately identified or dated. Grey Belgian pottery was poorly represented, as in nearby Mogorjelo, suggesting that it was not typical of this part of the world.

Pompeian vessels, which appear in the west mainly during the 1st century, were also represented by a few sherds (red clay fired at high temperature with inclusions of quartzite, similar to later Slav pottery, from which it differs in its greater purity of fabric and higher firing temperature). These date from the earlier period, 1st to 2nd century.

Red ware with a white slip constitutes another group of fine ware, forming a distinct group in both workmanship and form (sherds of pitchers, bowls and pots, on most of which traces of the white slip, albeit discoloured, had survived). Most of the red wares with inclusions of mica (glimmer) were thin-bodied, and had been fired at high temperature. As to date, these wares probably remained in use over a fairly long period, from the 1st to the 4th century.

Sherds of red-slipped pottery, usually with a light body, were fairly uncommon.

Byzantine pottery first made its appearance in the Mediterranean in late Antiquity. It has an uneven, ridged surface, and has no analogy in northern Europe. It is found in Italy and the Balkans, and is usually called Byzantine because it was the most common type found here during the Byzantine period. In Italy it dates from the 4th and 5th centuries. There are signs of this technique on some of the sherds in Višići, on light-coloured or red pottery. Most of the sherds with ridged surface belong to the globular cooking pots known as olla, the most common type in Italy. Fragments of large red vessels with close-packed, sharp ridges, common in castra and also found in Mogorjelo, also belong to this group of uneven-surfaced pottery(38).

(continues here)

There were few epigraphic finds in this large villa: just two graffiti inscriptions on potsherds and a factory stamp on a large piece of sheet lead (25 x 30 cm).

1. Graffiti (on a sherd of light red pottery) with the name AEM(ilius) LICIN(ianus), was found in room 9 D, and is the name of a private individual or worker. The same genticilium also features in Narona.

2. Graffiti (a name on a sherd of terra sigillata chiara) with the name OL(...) BEN(e)F(iciarius) ERB(oni) (centurionis)

3. A factory stamp on a piece of lead pipe or cauldron, with the letters I(d)IUS EUCA(r)P(us)

Numerous coins were found throughout the ruins (inv. no. 12.827-12.858), ranging in date from 104 to 383 CE, the same time span as the other finds in the villa.

Finds of later periods

Evidence of habitation on the site of the Roman villa after it was abandoned and fell into ruins was also found. Once it has been destroyed at the end of the 4th century, the local residents began burying their dead in the ruins, and with the arrival of the Slavs, a Slav settlement took shape in the ruins, with its own burial ground. As a result, the remains of a burial ground dating from late Antiquity, a Slav settlement and a Slav burial ground were found.

The late Antique graves were not laid out in any particular order or orientation, and were located in the part of the villa that was probably in the most ruinous state at that time (buildings A and B). There were two types of grave. The skeletons of two children were buried in Roman amphorae, one – B, by room 6 A, the other – B, by room 8 B. A number of graves of Roman brick laid to form a roof (A 1 and A 2 in court I, A 7 in room 19 C) were found by these amphorae burials. None had any grave goods. Graves with roof tiles laid to form a roof are to be found in Roman times as well, in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, with modest grave goods. Both types of grave continued in use until the 4th century.

Slav settlement

There is extensive evidence of temporary hearths and of some masonry hearths in the village, suggesting that the Slavs used the ruins of the villa in Višići as a refuge for some time. They seem to have taken up residence in building D, since it was only here that masonry hearths were found, along with a thick, black layer of organic waste around them. In addition, evidence of temporary hearths, in the form of a thin red layer of burnt soil in places, was also found. (continues here)

Legal status to date

According to the Institute for the Protection of Monuments of the Federal Ministry of Culture and Sport, the archaeological site of the Roman villa in Višići, Municipality Čapljina, Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, was registered as a cultural monument in the Register of immovable cultural monuments of SR BiH pursuant to Ruling no. 05-TB-772-1/66 of 27 May 1966.

Research and conservation and restoration works

C. Patsch singles out the site known as Kućišta in the village of Višići near Čapljina from the numerous Roman sites in the lower Neretva valley, on account of its large size(46).

The site was reconnoitred in 1955 by the then director of the National Museum of BiH in Sarajevo, Prof. Marko Vego, who established that this was an important property with mosaics and murals. Archaeological investigations led by I. Čermošnik were carried out from 1956 on.

The movable archaeological material is stored in the National Museum of BiH in Sarajevo.

Current condition of the property

The findings of an on-site inspection conducted on 4 June 2009 are as follows:

There is nothing to indicate that there was a Roman villa here. Few of the local residents know that there was one there or that archaeological excavations were carried out. Houses have been built over it and orchards planted, and the fields are ploughed. The soil in the ploughed fields was rain-soaked, and no surface finds (tesserae and suchlike) could be observed.

(Excerpt from Bosnia and Herzegovina Commission for Preservation of National Monuments - Roman villa (villa rustica) in Višići, Municipality Čapljina - National Monument of Bosnia and Herzegovina)

The archaeological site consisting of a Roman villa (villa rustica) in Višići (at “Kućišta”), with remains dating from Roman antiquity and the early and late mediaeval period (a Slav settlement and burial ground), Municipality Čapljina - National Monument of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Location

The Roman villa rustica at Kućišta in the village of Višići is located at an altitude of 20 m above sea level, latitude 43° 03.75.3' and longitude 17° 42.972'.

The National Monument is located on a site designated as the following cadastral plots: c.p. no. 821/1 and c.p. no. 821/1, title deed no. 910, c.p. no. 822/2, c.p. no. 823, c.p. no. 824/1, c.p. no. 824/2, c.p. no. 825, c.p. no. 1949, c.p. no. 1951/1 and c.p. no. 1951/2, title deed no. 858, c.p. no. 838, c.p. no. 840 and c.p. no.. 841, title deed no. 936, c.p. no. 839, title deed no. 613, c.p. no. 842 and c.p. no. 843, title deed no. 521, c.p. no. 862, title deed no. 249, c.p. no. 863, title deed no. 238, c.p. no. 1938 and c.p. no. 1939, title deed no. 11, c.p. no. 1940, title deed no.10, c.p. no. 1941, title deed no. 12, c.p. no. 1950, c.p. no. 958, c.p. no. 832 and c.p. no. 834/1, title deed no. 987, c.p. no. 826/1 and c.p. no. 826/2, title deed no. 203, cadastral municipality Višići, Municipality Čapljina, Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Historical background

Modern-day Čapljina is on the Roman road that ran along the Neretva valley from Narona(2) to modern-day Mostar. It was a sizeable Roman settlement, as confirmed by the ruins of Roman buildings, and numerous finds of antique coins(3) and imported pottery. The proximity of Narona and the favourable geographical location contributed to the growth of the Roman settlement in Čapljina, which became a trading and communications centre for the surrounding areas. There were sizeable Roman settlements along the Neretva to the north of Čapljina in Dretelj, near Počitelj, and in Žitomislići. The entire area from Čapljina to Narona and Hutovo Polje was one of the most densely inhabited areas of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Roman times(4). Narona, a Roman colonia in the southern Adriatic, extended back deep into the hinterland, its ager covering almost the whole of modern-day western Herzegovina. To the west, it extended to the Imotski polje, where it marched with the municipium(5) of Novensium (Runovići near Imotski), and to the north-west with Delminium (the municipium of Delminensium) in the Duvno polje, both in the lands of the Delmatae tribe. The municipium of Diluntum (Diluntinum, Stolac) was on the left bank of the Neretva. The colony's large area was probably subdivided, for ease of management, into smaller units or prefectures, and later into pagi (sing. pagus). These were in fact small natural entities, the location and extent of which can be deduced from the lie of the land (Ljubuški, Brotnjo, Čapljina, Cim). The entire area was under central administration from Narona, where the senate (ordo decurionum) had legislative and administrative authority over the colony's entire ager. Representatives of out-of-town decuria (decuriones) also came to the council; at first, these were mostly large landowners, but with time they were joined by a few local notables(6).

The process of Romanization and urbanization, which began in the lower Neretva region a full century and a half before it reached the hinterland (the upper Neretva and Bosnia), peaked in the 2nd century CE. The development of urban settlements, one of the most significant forms of Romanization, began here in the 1st century CE (Narona, Humac, Posuški Gradac, Stolac, Tasovčići, staging posts etc.). New building techniques, forms and structures were used, unknown in the region before the Romans introduced them. The traditional timber and dry-wall structures were replaced by new materials (lime and mortar, cut stone, fired brick and so on). Evidence of the early presence of Romans in and around Čapljina is provided by an inscription from Tasovčići, erected in 36/35 by the brothers Papii in honour of Octavian (CIL III 14625), which is also the earliest Roman inscription yet found in Bosnia and Herzegovina(7).

Numerous Italic-type settlements took shape throughout the colony of Narona, most of them during the early Empire. There are settlements of this type around Ljubuški, Čapljina and Čitluk, with some around Grude, Posuški Gradac and Široki Brijeg, as well as by the Radobolje near Mostar, with its centre in Cim and Ilići. The most common type of structure in these groups of buildings is the villa rustica, forming the centre of a smallish farmhouse estate (fundus, praedium); such estates would sell their surplus on the market. In time small-scale manufacturing also developed on such estates, usually brickworks (figlinae), producing tiles and bricks, for which there was a great demand, but also those of other trades – stonemasons' yards, smithies, carpenters' workshops etc. Very few of these commercial estates have so far been excavated: one that has, is the large villa in Višići near Čapljina.

Description of the property

Remains of the villa

The villa as so far excavated consisted of a number of buildings, including the lavishly appointed main residences occupying the central area of the estate. These were interconnected, surrounding courts of various sizes. On the outer edge of the group of buildings was a boundary wall wherever there was an open court, sometimes quite large. The courts have been excavated only to the extent of small soundings along the walls. The complex therefore consisted of a group of buildings, some detached, forming a separate entity, usually separated by walls. The first group of buildings, to the north-east, surrounded a brick kiln and open area I (building A). The next was a peristyle building(8) (building B). A building with a hypocaust(9) (building C) extended from the south-east corner of building B; beyond building C was court IV, with workshops. The south wall of court IV continued eastwards, enclosing court V facing the south façade of the peristyle building. A range of buildings led from the north-west corner of the peristyle building to a building D, the northernmost building of the villa. Building D consisted of a long building to the south, probably the bath suite, and adjoining buildings to the west and north, forming a U-shape surrounding a square court and thus dubbed the “U-buildings;” all three had a portico facing onto the court, which interconnected them(10).

In this group of buildings, the main, lavishly appointed buildings (B, C and D) were all oriented south-east/north-west, and reveal a tendency towards architectural regularity and symmetry. Seen as a whole, however, the group does not convey a sense of symmetry, since the walls of the service quarters were not in line with those of the main buildings. This layout was no doubt dictated by the practical needs of estate management.

The purpose of the various groups of premises could be determined only on the basis of their surviving architectural remains and any finds made within them. In places, especially around the outside of the villa, the ruins of the walls had been much dispersed, and the Slav settlement and burial ground had caused significant damage to some of the buildings, which is why it has proved so difficult to shed light on the architecture of the villa in Višići.

Judging from the surviving walls in building B and, to some extent in building C (elsewhere, only the foundations survived), the walls were of fired brick and the foundations, which were 50 cm wide, were of rounded stones set in a conglomerate of mortar and gravel. The foundations were 60-70 cm in height except in the case of the hypocaust, where they were higher, to accommodate the height of the pilae stacks. The walls were of wedge-shaped bricks laid in courses, known as opus testaceum, using the large bricks known as tegula bipedalis, set with their long side outwards, framing a core of mortar and gravel. This type of brickwork was common in Rome from the reign of Claudius(11) (1st century) onwards, and remained in use until the late 2nd century. Part of the wall had survived in the south-east corner of the south façade of the peristyle building, enough to conclude that the south façade had been built in opus reticulatum, using small, diamond-shaped bricks. Like opus testaceum, this technique also first appeared during the reign of Claudius, and remained in use until 180. This wall belonged to a later stage of construction, being used for only one side of the building. By Vespasian's reign(12), only prominent wall faces were built in this technique, and from Trajan(13) to Aurelius(14) the use of opus reticulatum gradually declined.

Building A

The group of premises forming the north-east end of the villa could not be properly excavated, since much of the group lay beneath family houses, and the remains of the easternmost premises had seemingly been swept away by the river that once flowed here, where the road now runs. Evidence for this can be found in the vestiges of walls on the opposite side of the road, in the fields, where the easternmost corner of the villa probably lay. The rooms of building A were separated from those of building B by a court, with only room 10 at the northern end of the court connecting them with the north and east premises of building B. A brick kiln divided building A into rooms to the south and others to the north, probably each used for different purposes. The four rooms to the south (1-4 A), faced in the same direction as the peristyle building. It was not possible to excavate their north-east corner, which lay beneath an orchard(15). The two oblong rooms at the south-east end were irregular in shape, with their north wall on the diagonal to accommodate the brick kiln, which was off true towards the west from the north-south axis, as were the rooms to the north. The two irregularly-shaped rooms (2 and 3A) where the remains of large vessels and amphorae were found had floors of lime mortar. Another two rooms (1 and 4A), which opened onto court I, had no flooring, but contained a layer of small lumps of reddish and yellowish unfired clay waste, roughly 10 cm thick. This group of rooms, like nos. 5 and 6A, were probably used as workshops associated with the brick kiln. The larger, 6A, belonged to the original building, while 5A was a later addition, as the walls built on a half-metre thick layer of rubble indicated. Quantities of potsherds were found in the north room, 9A, probably rejects from a pottery, since they included two bases of vessels that were not up to standard. The finds in the south rooms were sufficient to provide a fairly clear idea of their use, but the use of those to the north of the brick kiln remain a mystery, particularly since they could not be excavated. All that could be traced was their west wall, which extended on by more than 15 m to building B, thereby forming the boundary wall of open area II outside the peristyle building and probably the bath suite (building D) as well. This group of rooms seem to have consisted of two ranges of rooms, of which only the first two (7 and 8A) could be excavated, in part. Since the level of the topsoil in room 7 was more than half a metre below that of the topsoil in room 8, and given that the circular bricks of pilae stacks from a hypocaust were found in the ruins, it seems likely that these rooms had a hypocaust, as did those further along, as suggested by the bricks of the type known as tegula mammata (which replaced the box flue tiles known as tubulus)(16). The hypocaust suggests that these rooms were used as living quarters, or perhaps as a kitchen, since they were close to the triclinium in the north wing of building B(17).

Room 10, which connected buildings A and B, differed from the rest. Its profile revealed that it had been used to store amphorae, probably holding oil and wine. Like all the open rooms, this had no flooring; above the top soil, at a depth of 150 cm, was first a 40 cm thick layer of sand, in which there were sherds of amphorae, the thickness of the layer indicating that the amphorae were set into the sand. This room must have been used a wine and oil store for building B.

The brick kiln occupying the middle of building A was quite large (5 x 10 m), square in shape, with a single central channel 50 cm wide and 30 cm high with six narrower side channels branching off. Only the substructure of the kiln had survived. The door for feeding fuel had been destroyed by three later Slav burials. The kiln is of the type used for firing bricks, as suggested by two large piles of unfired roofing tiles (imbrices) that had become fused together, found not far from the kiln in the portico and garden of the peristyle, and by the remains of clay in the workshops next to the kiln. No waste matter of the kind that could have provided firm evidence for the type of wares fired here was found around the kiln itself. Square kilns were not used only for firing bricks. Square kilns have been found in Helvetia(18) and Pannonia that were used to fire pottery. Square pottery kilns predate circular ones, found for instance in Germania, and first appear in Pompei in the 1st century BCE, whereas circular kilns appear only in the 2nd and 3rd centuries. A square kiln found near the Ali Pasha mosque in Sarajevo was probably also used to fire pottery(19). Since the upper part of the kiln in Višići had been completely destroyed, it is impossible to say whether it was also used to fire pottery.

Building B

Building B – the peristyle building – proved to have the usual regular layout of rooms around a central garden: one range of rooms to the east and one to the west, and two to the north, with a narrow portico on the north and south façades. Judging from the small surviving area of wall at the east corner of the façade, the south façade was faced on the outside with small diamond-shaped bricks in the technique known as opus reticulatum. The roughly square open central area of the building (13 x 14 m) had no floor, and might have been a garden. It had a double wall, the outer probably forming a base for the columns of the portico, and the inner, 20 cm lower than the outer, either a retaining wall or a step. None of the stone fittings of the portico and garden were found here, and neither were any vestiges of the peristyle columns, apart from a fragment of a single column with a diameter of 13 cm. Most of the artefacts found in this complex appeared to have been brought from elsewhere. Artefacts found in the 15 cm thick cultural layer about 150 cm below the surface consisted of both Roman and Slav articles intermingled, potsherds, tools, pieces of Slav jewellery and a semicircular bronze seal with the name of an officina (workshop), MAXENTIA, no doubt from the workshops, like the lump of waste from roofing tiles.

The garden was surrounded by a colonnade of which the quite badly damaged floor consisted of a 30 to 40 cm layer of sand topped by rammed fine-grade crushed brick. This was probably level with the mosaic floor.

The living quarters surrounding the garden were elaborately decorated. Most of the floors were of mosaic, and there were murals and stucco friezes on the walls, which had marble-clad dado panels. The corridors had simple mosaics with blue designs. The floors in the rooms were in polychrome, except for rooms 4, 6, 8, 11 and 15 B, which had floors of lime plaster, though the walls were elaborately decorated with murals and marble cladding. It is possible, therefore, that the floors were plastered when the mosaics were damaged, as happened in rooms 7 and 8, originally one room.

The mosaics are certainly the most valuable survivals in the rooms, being in a better state of preservation than the murals, enough to be reconstructed. The only mosaic that was completely destroyed was the one in room 4B, though those in rooms 1, 2 and 23 B were quite badly damaged; the others were damaged only in places. In room 18 B, later repairs to the mosaics were observed, where damaged areas had been filled with larger tesserae than were originally used.

The architecture of this building showed a tendency towards symmetry, with the east and west ranges of rooms of the peristyle almost identical in layout and size. This symmetry was also reflected in the principal motifs of the mosaics, with any monotony in the repetition avoided by the choice of different designs as fillers. In rooms 2 and 23 the central motif was a circle with a rosette with rhomboid lobes. In rooms 3 and 22 the central motif was again a circle, filled with a diamond pattern (room 3), or with a fish-scale pattern (room 22); in each case, the centre is occupied by fish on a platter. The corresponding corridors, 5 and 19, had a simple pattern of small crosses. Rooms 17 and 8 had a design consisting of a central circle filled with seven hexagons. The north rooms of building B again feature symmetry. The largest room, in the middle, was the triclinium, with an elaborate mosaic floor; its size, central location and lavish decoration highlight its importance as the main dining and banqueting hall. It was flanked on either side by two symmetrical rooms and a corridor, where the motif consisted of diagonal interlocking circles. The floors of the two facing rooms by the colonnade were of lime plaster (11 and 15 B), while the ones by the north porticus (10 and 16 B) had mosaic floors with designs based mainly on squares.

It was not possible fully to determine the circulation from room to room in building B, since not all the walls had survived to above floor level, and in places neither had the thresholds. The only indication of the construction of the thin partition walls, which were largely ruinous, was the remains of two sizeable blocks that had survived in the layer of rubble on the floor in rooms 10 and 11 B, consisting of pieces of thin roofing tiles laid diagonally in a thick layer of mortar. Doorways were identified between rooms 1 and 2, 5 and 6, 7 and 8 B and 8 and 10 B, as well as one between the corridor and the colonnade, in the case of the east rooms. The central room to the north had four doorways opening onto the side corridors direct from the portico.

The symmetry of the east and west rooms of building B was disrupted by the small rooms at the west end of the west rooms. Most of these appeared to have served the same purpose, to provide indirect heating for the west rooms against which they abutted, since the pilae stacks of a hypocaust were found in them. Rooms 22 and 23 B ended in the form of apses, connecting to the point at which the hot air vents met. The praefurnium had not survived.

Another group of four small rooms, all quadratic in plan, occupied the north corner of the west rooms of building B. The first three rooms consisted of a central longer room without flooring (28 B), flanked on either side by small rooms both of the same size, with the pilae stacks of a hypocaust. The room with the pilae stacks had a vent opening into the large room in the middle, which probably provided direct ambient heating. The fourth room (30 B) was of the same small size; at the extreme north-west corner of the peristyle building, it was used as a privy, and had a flooring of large flagstones. Another small room, a later extension, also formed part of this range, and was used as a kind of passageway from the corridor into open court II.

The elaborately decorated rooms of building B were no doubt used as reception rooms and as dining or banqueting halls, as suggested by finds of terra sigillata chiara and shells(20).

Building C

This residential hypocaust building, quadratic in plan, could not be isolated from the other rooms with court IV, forming as it did the north-east corner of that building. Abutting onto it were rooms leading onto the court and surrounding service quarters. There were also three small rooms by the square room; it proved impossible to determine whether they were connected with building C or had had some other specific purpose. The small south room, 12 C, was heated by the hypocaust of this building. The flooring in the rooms of this building had suffered more than those of building B, since the level of the hypocaust was somewhat above that of the rooms in building B, which was one of the reasons why not one floor with pilae stacks had survived. Here too the flooring above the pilae stacks had not survived, and only some remains of the pilae stacks themselves remained. Even the floors of the rooms with no pilae stacks were badly damaged, being only half a metre deep in fields that were regularly ploughed. In rooms 2 and 4 C, only the base for the mosaic had survived; the tesserae were found in the rubble below the floor. The floor of room 5C was at the same level; fragments of its lime plaster flooring were found in the rubble. Rooms 10 and 11 C with pilae stacks would seem to have had mosaic floors, given the number of tesserae and fragments of red wall painting that were found in the rubble between the pilae stacks. Only the small room above the praefurnium had no flooring, being used to fuel the praefurnium.

The substructure of the hypocaust rooms were better preserved. The praefurnium, with a flue providing direct heating for room 10 C, also provided heating for rooms 11, 1a and 12 C, which were interconnected by hot air flues in the walls. Later the flue in room 11 C was bricked up. In all these rooms the pilae stacks of the hypocaust were of circular bricks with a diameter of 20 cm, except for the pilae stacks against the west wall of room 1 C, which were of square 30 x 30 cm bricks.

Judging from the hypocaust and its fittings, the mosaics and the murals, this would certainly have been a dwelling house, as further evidenced by the construction system of the hypocaust. The praefurnium flue was not by the bath suite, outside the room, but was built into the first room itself. Setting the pilae stacks of the hypocaust right by the wall made it impossible to use tubuli(21) by the wall, essential in bath suites to protect the murals from damp. Another opinion is that the tubuli were used not only to damp-proof the murals but also to heat the walls. It is not clear what the rooms heated direct without a praefurnium were used for, such as rooms 9 C, 27 B and 29 B. They are thought to have been small supplementary hypocausts to provide greater heating for a given room, which would correspond to the use of the small rooms on the west side of the peristyle in Višići(22).

The way the hypocausts in Višići were constructed matches that of the third, more advanced stage in the development of the hypocaust. The bricks used were extremely heat-resistant, making it possible to achieve very high temperatures, sufficient for one praefurnium to heat as many as four rooms. Hypocausts of this type were first built in the late 1st century.

The hypocaust building formed a single entity with south-west court IV, forming as it did the north side of the court, along with the room with a well. The east wall of the court was an extension of the east wall of room 12 C, and the west wall an extension of the west wall of the room with a well (8 C). A range of large rooms, 14 m in width, 21 to 24 C, abutted onto this west wall. The south wall of the complex could not be traced for technical reasons. All that survived of the walls of the large rooms was the lower course of rounded stones of the foundations, as in the other outer rooms of the villa. The cultural stratum was poor; just a few potsherds were found.

The finds in the other rooms around the court revealed that there were workshops here. Large estates such as this one in Višići always had all the workshops needed for the household. Some could not be traced, since the Slavs had dismantled all the fixtures in the buildings and used them to build a hearth in building D, in the north-west corner of the villa complex (the bath suite). Judging from the remains in this court, the workshops here would have been used for preparing clay, and would also have included a forge and other workshops. This was suggested by finds in the narrower part of the court, by room 8 C, of iron stoneworking and woodworking tools, a bricklayers' trowel, and pieces of slag – waste from a forge. Fragments of amphorae, unfired potsherds and blocks of fired earth were found in room 13 C, suggesting that this was a pottery, which the Slavs later completely destroyed: the lower stratum contained not only Roman pottery but also sherds of Slav pottery and the remains of children's skeletons. A range of small rooms (14 to 20 C) in which a 20 cm thick layer of clay waste, green and yellow in colour, was found, would have been used for preparing the clay. These rooms were next to the room with a well (8 C), from which the workers would have drawn the water they needed. The stone well was square, and covered with stone slabs, only those by the west corner surviving.

There was no sign of flooring in any of the rooms in these service quarters, which probably had lime plaster floors.

Building D

The third dwelling house, with its elaborate stone furnishings, formed part of a group of buildings surrounding three sides of an open square space and connected by an inner colonnade. The main building was connected with building B by a range of small rooms. Here the walls, which were 20-30 cm thick, were of poorer construction than in the other buildings. This poorer construction, the finds of pieces of amphora, potsherds, pestles and mortars, and shells, suggested that they formed the kitchen quarters, or were storerooms. In building D, the main building stands out on account of its elaborate stone furnishings, its architecture and its use, and appeared to have been self-contained. The west and north buildings of building D, forming an extension of it, would appear from the finds to have been much less important.

Evidence for the existence of a bath suite in building D is provided by the substructure of a hypocaust and a water supply system. Since the flooring of the substructure was missing in almost every room, it was possible to deduce only from clues whether certain rooms had pilae stacks. In the large room, 9 D, which had a range of small rooms to the north and south, the lime plaster flooring had survived in two small rooms to the north (4 and 5 D) and in the oblong room at the west end (10 D). The depth of this flooring matched that of the flooring of the substructure of the hypocaust rooms of building C. Circular brick stacks were found on the floor in room 10 D, probably in situ. No evidence of a praefurnium was found; it was probably outside the building, as in the case of every bath suite. Coarse mortar with an admixture of finely crushed brick in the surviving foundations in room 10 D suggest that there was no floor at this depth. The walls of the room, however, were painted, as revealed by the remains of red wall paint on a small area of the wall of the latter room.